Whenever I was home sick as a girl, my mom would leave me with a pile of VHS tapes I was expected to watch instead of Maury and Judge Judy. There was one from the 1950s about an English missionary to China, some of the original, hand-illustrated Disney flicks, and then two versions of Little Women. Barring one exception, I always chose Little Women, in particular the 1994 version with Winona Ryder and Claire Danes.

Though our home was a very religious one, the most transcendence I experienced was from watching that film. For years, I slipped a hat over my head and ate orange slices like Jo March, all while “languishing” over my first full-length murder mystery novel. I sifted through a plastic garbage bin full of dress-up clothes pretending I was Amy or Meg; too poor to be ravishing but too pretty to be totally invisible. Or I was at the piano, like Beth, serenading the house while slowly dying of something no one could see but me.

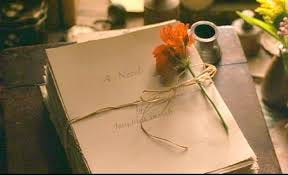

My favorite scene was always the same: the moment when Jo, after years of failed attempts, finally finished her manuscript. She ties the thick stack of handwritten papers with some brown string and slides a red gardenia through the center, stepping back from the work with a smile on her face. She has finally done it—created something honest—and she knows it.

Like Jo, I first told every version of my story except for the one that was true. I knew only one thing when I began my food memoir six years ago: the kitchen was the only place I did not regret spending my time. I wanted to know why.

I am tempted to say that I was a basket case when I first started cooking, but that feels like an insult to baskets everywhere and it also isn’t the full story. The truth is that I was wounded. After a decade of chronic childhood sexual abuse and just as much time spent trying to hide it, I was too broken and tired to do much else but function. That was difficult for quite some time. I got married at 26 and bam, out slid all my trauma. Minutes felt as long as days in the face of unrelenting PTSD. I began to think my husband would have fared better if he had married a potato. I had no sense of self and no reason to hope that things would ever be otherwise. Whenever a fragment of who I truly was did resurface, it seemed ugly, vulnerable, perverted, guilty, or too needy for me to satiate.

I stepped into the kitchen hoping for a peace I no longer felt within myself. But cooking, as it turned out, was hard. Real hard. Everyone who was good at it had grown up with happy memories of mom or grandma or auntie or dad flipping pancakes or shelling peas. I had some, but these were often tainted by the undercurrent of abuse and dysfunction simmering below a very slick family veneer. And then there were the words, the dismissive, culinary, high-falutin terms like “dash” and “brown” and “simmer” and “macerate.” So I struggled, both with myself and with my truly galling lack of cooking acumen.

There was no lightbulb moment. Time simply passed and slowly I observed things that had always been lost on me. I learned that chicken is toxic when eaten raw but nourishing when basted in butter and cooked gently at a very low temperature. I learned that stinging nettle will burn and poke unless blanched and sautéed with some sausage. I learned that when you combine flour and water to make bread, you create a final union of matter. I learned that some transfigurations are so final that they become blessed, even by God.

More importantly, I learned that life, however sore and tired, bizarre and banal, is always good enough to eat. One of my best dinner ideas came from an alcoholic grandfather who told me he ate poor man’s tomato soup growing up. Just ketchup and water, he said, and there it was: inspiration. Another idea came from the Chipotle takeout we ate in the years when everything I made burned or congealed. Still another was found in a box of Mac-n-Cheese made by a childhood best friend (it was Annie’s, of course). Then there was the stock I made in the months after my mother-in-law’s death, one of which, ahem, included a potato and leftover salsa verde?

Some things come perfect and cheap and can truly not be improved upon. The McDonald’s hot fudge sundae, for example, is a work of art you can eat any day of the week for just $3.65. Other things take time and expense and a part of ourselves that already feels weary. Knowing the difference has nothing to do with whether or not Mom knew how to pickle cauliflower or make sourdough baguettes. Mine reheated frozen bags of Bertolli rigatoni and, on special occasions, Digiorno’s pizza (both of which still slap, by the way). More than sufficient, if you ask me.

Finding one’s path in the kitchen, I learned, is not about being born special. Being born is special enough. Finding my voice was as easy and as difficult as learning to love the life I had already been given: Pain and disappointment included. Whenever something is loved and accepted for what it is instead of punished and chastised for what it isn’t, something like beauty emerges. Something like us.

It was this lesson I took with me into the rest of my life, and slowly, over ten years, something in my broken heart blossomed.

Today I sent my manuscript to my editor. There was no antique twine or gardenias. And unlike Jo and Professor Bhaer, I’m not secretly in love with Lo (or am I?). But there was peace. And after ten long years—joy. Aftertaste (my book!) is everything I’ve learned about home—that it’s not a destination after all, but a decision to accept life and the inner voice as it truly comes to us. I thought of Jo a lot this week, and I thought of that little girl I once was, so eager to tell a story that would change the world, never knowing that the life she already had was exactly that.

Though I do not know what the future holds for my little book, I do know this: ten years ago I prayed for the ability to string two sensical thoughts together. And now look at me. I do know how to cook. My husband did not divorce me to marry a potato. And I have a 60,000-word document to prove it. I might even go to McDonald’s to celebrate.

Edits by Lauren Ruef.

SHUT UP YOU DID THE THING!!!! And it was hard. And I bet you wanted to burn it to the ground 1,000 times, but you did it!!!! So proud, and I cannot wait to buy my own copy!

You have spun trauma into a feast, which is no small feat.

And I have to say, the scene with Jo and her book also inspired me more than any other movie scene ever. I thought of her the very moment I held my book for the first time (the linen bound, silver embossed copy that I always dreamed of).

May your book have legs and wings to reach many hands and many counter tops. May it be sprinkled with flour and splashed with gravy bits as people try your recipes.

You’ve done it. You made magic.🎉

I hear strength and resilience here. Cooking was fighting for life and joy for you. These words you’ve penned matter and inspire me. Aftertaste sounds like the perfect title after reading what I’ve read here. Rooting for you!